By Tony Wolf

During late January of 2020 I returned to snowy Chicago from a three-week long vacation and family reunion in sunny New Zealand. During the trip we’d celebrated my mother’s 80th birthday with a surprise party and also received the devastating news of a death in the American branch of the family. At the same time, there were ominous reports from China about a new, highly contagious and potentially deadly coronavirus disease.

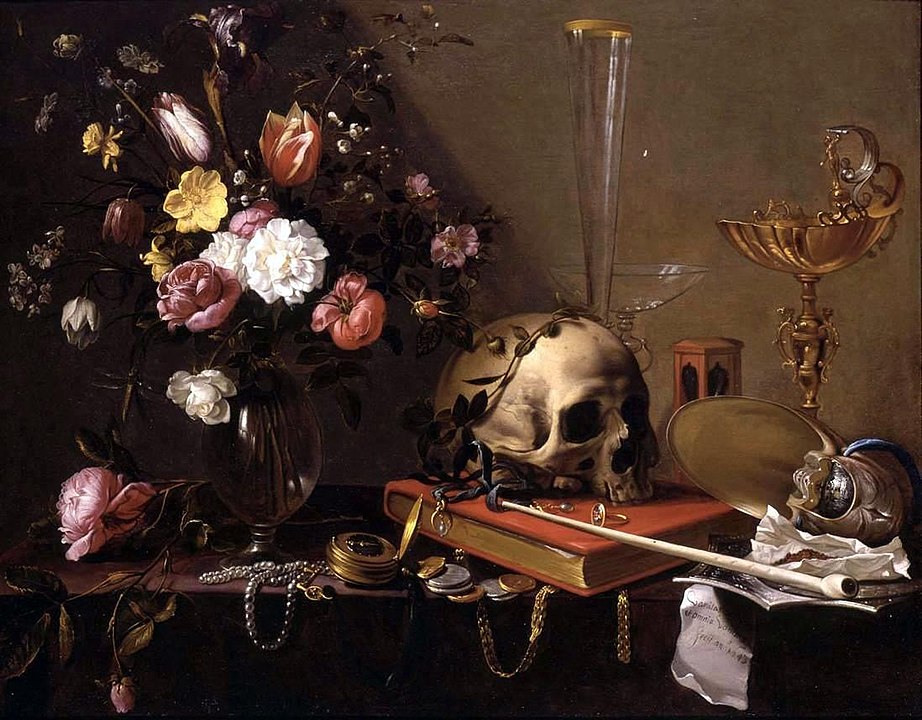

About a month before the COVID-19 lockdowns began, with mortality on my mind and an urge to make art, I started collecting objects inspired by the symbolism of vanitas paintings.

During the 17th century, artists would carefully select and assemble items with an eye towards illustrating the impermanence of three earthly modes of being – the vita voluptuosa (life of pleasure), vita contemplativa (life of contemplation) and vita activa (life of action) – in oil paint.

We already owned some suitable items – a brass compass, a simple ceramic bowl, a selection of antique books – and I bought some others, including an hourglass, a set of three wooden dice and an ornate sea shell.

The notion of the shrine is to bring vanitas symbolism back into three dimensions as a form of secular assemblage art, inviting daily contemplation on the interplay between life and death. The shrine occupies the space of a single bookshelf in our living room.

The vanitas shrine and associated practices are works in progress, including the practice of finding small items to add to the shrine during my evening walks. I’ve found that this habit transforms the walks into a kind of dérive – mindful drifting with the aim of getting lost, in some sense or other, to experience or learn something new. When the leaves start to fall this coming October, I’m planning to incorporate memorial elements from the Dia de Muertos tradition of the ofrenda into the vanitas shrine by displaying photographs of deceased family members and friends.

The entropic vanitas aesthetic has much in common with that of the Japanese wabi-sabi philosophy, which favors humility, rusticity and the imperfection of time-worn and hand-made objects. Vanitas shrines require an investment of creativity but they don’t require much of your time, nor money, and I can firmly recommend making your own if you feel so inclined. Please feel free to get in touch via the comments and I’ll be happy to offer any advice or feedback that may be useful. In the meantime, here are some resources that I’ve found inspiring:

How to Altar the World: Amalia Mesa-Bains’s Art Shifts the Way We See Art History

These Lush 17th-Century Paintings Were Striking Reminders of Mortality