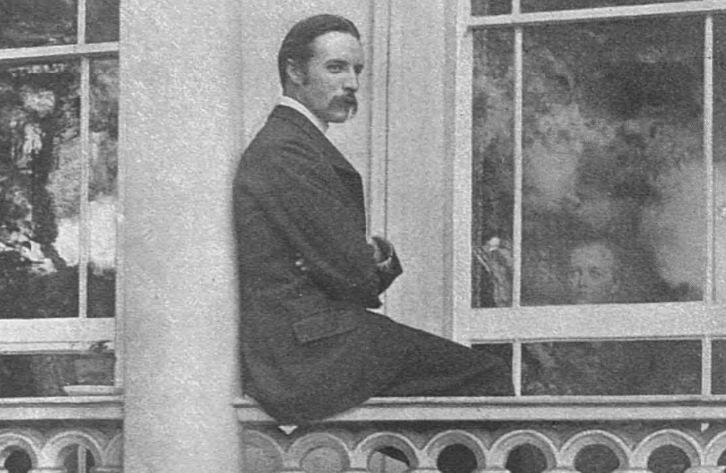

During August of 1893, the recent publication of a suicide note by a young Englishman named Ernest Clark sparked an impassioned letters-to-the-editor debate upon the philosophy and ethics of “self-effacement”. A missive by the prominent Scottish writer and theatre critic William Archer outraged those of less bohemian sensibilities – including G. K. Chesterton – by not only arguing in moral favor of the act, but also proposing state-sponsored “lethal chambers” within which people could end their own lives with a minimum of pain and fear.

Archer’s darkly imaginative rhetoric follows:

No doubt there are some people who, on religious grounds, regard suicide as a “sin”. I don’t know where it is prohibited in Scripture. I look up the index to the admirable Oxford University Press Bible and find no mention of it; but Hamlet says that the Everlasting has “fixed his canon ‘gainst self-slaughter,” and I suppose there must be some authority for the statement.

That view of the matter, at any rate, is inculcated in some of the noblest lines ever written in the English language – this speech of Dryden’s Don Sebastian:

Death may be call’d in vain and cannot come,

Nor has a Christian privilege to die.

Brutus and Cato might discharge their souls,

And give ’em furlough for another world;

But we, like sentries, are obliged to stand

In starless nights, and wait the appointed hour.”

There; are not these last lines beautiful! They move me like a great Handelian melody; I cannot transcribe them without tears. And for my part, indeed, I most potently believe the sentiment they express, only I hold that Ernest Clark (the suicide) awaited the appointed hour no less than Methuselah or M. Chevreuil.

This, however, is a quibble, and the people who hold suicide a “sin” must be left in the comfortable enjoyment of that conviction. He put out the candle resolutely, expeditiously, effectually, and, we may hope, almost painlessly. It is the people who bungle the thing that are to be pitied, or who drag on in misery because they know of no safe and convenient means of exit. What we want – what our grandsons or great-grandsons will probably have – is a commodious and scientific lethal chamber which shall reduce to a minimum the physical terrors and inconvenience of suicide, both for the patient and for his family and friends.

In a rational state of civilisation, self-effacement should cost us no more physical “screwing up of courage” than a visit to the barber’s, and much less than a visit to the dentist’s. The mental effort will always be severe enough to keep people from wantonly and in mere caprice putting an end to themselves. Of course there might have to be some sort of formalities about the use of the lethal chamber. As yet, we can scarcely foresee the day when there shall be an automatic electrocutor on every railway platform, and one need only stand on the foot rest and put a penny in the slot.

Perhaps it would be incumbent on the “intending suicide,” in the absence of a doctor’s certificate, to publish the banns, as it were, and allow a statutory time for the allegation of any just cause or impediment while he should not shake the yoke of inauspicious stars from his world-wearied flesh. There may be particular circumstances in individual cases which would render suicide an act of gross selfishness and inhumanity to others, though such circumstances would be of comparatively rare occurrence in an economically well-ordered society, and one in which the half-hypocritical sentiment against suicide in the abstract had been suffered to die out.

But except perhaps in cases of commanding genius, society, as such, has no interest in forcing any individual to remain in existence against his will. No one is indispensable. From the point of view of society at large, there are perhaps not 50 people in the world at any given time of whom it may not safely be said that their room is at least as desirable as their company. Society may rightly do its best to, prevent a man from leaving his remains about in an unsightly condition, to the inconvenience and discomfort of the lieges. But repressive laws do not, and never will, achieve that end. I do not believe any man was ever deterred from suicide by the reflection that it is a felony.

How much more rational to provide the man who is tired of life with a place and mechanism for putting his body away in a decent and self-respecting fashion! Why not have a crematorium attached to every lethal chamber, the whole under the supervision of the sanitary committee of the Parish Council?

It is my firm intention to die in my bed, of mere old age, somewhere about 1960. But, if circumstances over which I have no control should frustrate that good resolution, what a comfort it would be to know that I could put off a burden grown too heavy to bear without unnecessary physical torment to myself and without making myself a nuisance to those around me! No doubt there is a certain snobbery in suicide as in everything else. Some foolish young people get it into their heads that it is in itself rather a fine thing, as Hedda Gabler would say, to “do it beautifully.” I daresay there are even people who, as one of your correspondents suggests, would kill themselves in order to get a sentimental letter into the newspapers. But because some people kill themselves from what seem to us trivial motives, is that any reason why we should insist that others, to whom life is an incurable agony, should drag it out to the bitter end?

The other day I heard a compassionate lady, who gives a great part of her energies to the prevention of cruelty to animals, relating with just indignation a case in which an injured horse had been left lying in the street for hours, two police-men idly watching it, and no one taking the trouble to put it out of its agony. We all exclaimed, quite sincerely, upon this horrible heartlessness; but I could not help reflecting how much better off horses are than men.

In this case, the vet did ultimately arrive, and the poor creature was given its release. But if it had been a man who, say, had tried to shoot himself and failed, the policeman would have taken him to a hospital, and there all the medical science of the day would have been devoted, not to shortening, but to prolonging his physical and mental sufferings, while, if he recovered, the law would have stepped in to make things still more unendurable for him. And then, think of all the incurable and agonising physical and mental-diseases in the world!

“Man’s inhumanity to man,” said the poet, “makes countless thousands mourn,” but I am not sure that his humanity is not crueller still.