Despite their distinct lack of streaming video options, the ladies and gentlemen of the late 19th century were not short of amusing and instructive pastimes. Late Victorian social media was centered around clubs running the thematic gamut from banal to whimsically outré.

During the 1890s, examples of the latter kind ranged from the Whitechapel Club of Chicago, whose exclusively male membership of literary newspapermen met in macabre digs befitting their notional president (Jack the Ripper), to the (ironically) short-lived Vampire Club of New York City, whose sumptuous dinners were enlivened (as it were) by haunted-house props including a giant, glowing-eyed bat bearing a human skull in its claws.

It was all in good fun.

Although the entire latter 19th century was rife with tongue-in-cheek “secret societies”, many of which enjoyed mock-supernatural japery, things had taken a decidedly twisty turn on the evening of September 13th, 1881, when Captain William Fowler presided over the first annual meeting of his new Thirteen Club. Gathered in Room 13 of Manhattan’s Knickerbocker (count the letters) Cottage, the 13 founding members sat around a coffin-shaped table adorned with 13 candles, beneath a banner emblazoned with the gladiatorial motto Nos Morituri te Salutamus – “we who are about to die salute you”.

Fowler’s professed mission in founding the Thirteen Club was to strike a blow against superstition. His devoutly rational clubmen quickly evolved an ingenious set of fate-tempting initiatory customs, such as entering meetings by walking beneath a ladder, ritually spilling salt at the dinner table and wearing tokens of mortality, such as tiny model skeletons or peacock feathers (bearing the “evil eye”) as lapel decorations.

These ingeniously-themed diversions, paired with the chance of convivial camaraderie with like-minded fellows, inspired Thirteen Clubs in many other cities. After the London Club was formed in early May of 1890, its founder, the writer and historian William Blanch, remarked to a journalist that:

“If there is anything in the transmigration of souls, I shall come back to earth and be a house-dog. They never worry, neither do I. Superstition causes worry, that’s why I hate superstition.”

“And you have not a tender spot in your heart, Mr. Blanch,” the reporter asked, “for any one, mild superstition?”

“Not one. I like May blossom in my house; I consider the opal a charming stone; I am happy if I see the moon through glass; I don’t care a button if I upset the salt; I always walk under a ladder; I—well, superstition be hanged!”

Oscar Wilde, however, was dubious. Replying to an invitation to attend a meeting of the London Thirteen Club, he wrote:

DEAR MR. BLANCH, I have to thank the members of your club for their kind invitation, for which convey to them, I beg you, my sincere thanks. But I love superstitions. They are the colour element of thought and imagination. They are the opponents of common sense. Common sense is the enemy of romance. The aim of your society seems to be dreadful. Leave us some unreality. Don’t make us too offensively sane. I love dining out; but with a society with so wicked an object as yours I cannot dine. I regret it. I am sure you will all be charming, but I could not come, though 13 is a lucky number.

Again, though Blanch made a ritual show of ridiculing Wilde’s bantering reply during subsequent Club meetings, their exchange was very much in the spirit of bohemian bonhomie that characterized the Thirteen Club phenomenon as a whole.

Oscar Wilde may or may not have been superstitious in a literal sense – though perhaps most likely not – and his opinions on religion seem, in some respects, to presage modern spiritual naturalism. In De profundis, his last prose work and the only writing he did in prison to have been published, he wrote:

When I think of religion at all, I feel as if I would like to found an order for those who cannot believe: the Confraternity of the Faithless, one might call it, where on an altar, on which no taper burned, a priest, in whose heart peace had no dwelling, might celebrate with unblessed bread and a chalice empty of wine. Everything to be true must become a religion. And agnosticism should have its ritual no less than faith.

With that in mind, Wilde’s brief and fundamentally playful exchange with Blanch serves to illustrate a subtle tenet of Poetic Faith.

Insofar as the Thirteen Club settled squarely on challenging/debunking superstitious thinking (within which, I think we can safely subsume pseudoscience, conspiracy theorizing and so-on), they were performing a salutory public service akin to that of the modern skeptical movement. Supernaturalist beliefs certainly have caused much actual suffering in the world.

That understood, however, Wilde clearly shared the sentiment of one of his poetic ancestors, Lord Byron, who wrote in 1823:

The Gods of old are silent on their shore,

Since the great Pan expired, and through the roar

Of the Ionian waters broke a dread

Voice which proclaimed ‘’the Mighty Pan is dead.”

How much died with him! false or true — the dream

Was beautiful which peopled every stream

With more than finny tenants, and adorned

The woods and waters with coy nymphs that scorned

Pursuing Deities, or in the embrace

Of gods brought forth the high heroic race

Whose names are on the hills and o’er the seas.

I think that Byron and Wilde both argued, not in favor of actual irrationality, but rather for a Poetic Faith that stands upon the bedrock of rationality while still partaking – almost wholeheartedly – in a kind of mystical, romantic impulse via the suspension of disbelief. That phrase was coined and defined by the poet and aesthetic philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1817, when he wrote of

… (transferring) from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.

Here’s a thought experiment:

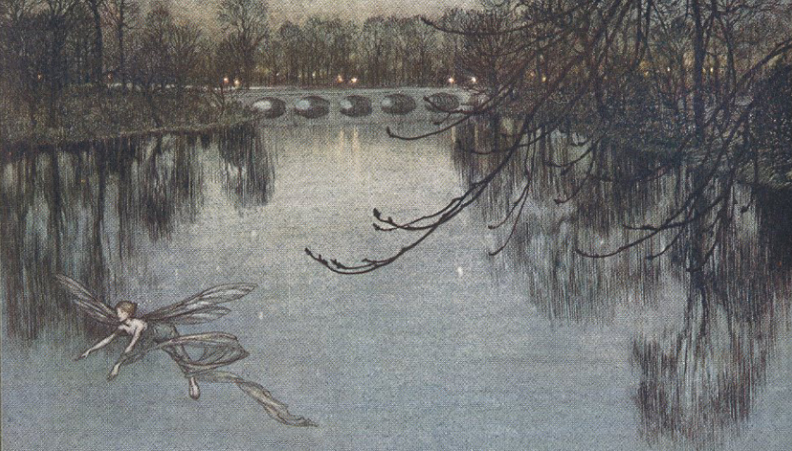

It’s the 27th of December, 1904 at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London. You’re seated in the audience of the inaugural performance of Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, by Oscar Wilde’s near-contemporary J.M. Barrie.

About half-way through the play, Peter Pan’s fairy companion Tinker Bell prevents him from accidentally drinking poison by swallowing the fatal elixir herself. Urgently, Peter breaks the fourth wall, turning to the audience and begging all children who believe in fairies to clap their hands, as it is only through this demonstration of belief that Tinker Bell’s life might be saved.

Do you applaud?

If you’d willingly suspend disbelief for that moment, then perhaps you have some sympathy with Oscar Wilde’s romantic resistance to the “offensively sane” ethos of the Thirteen Club.

Good article. But remember that Oscar Wilde became catholic and pro Pope in his last letters. We cannot understand Wilde without humor.

While Wilde famously fulfilled his long-term pledge to die a Catholic (“The Roman Catholic Church is for saints and sinners alone – for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do.”) – being received into the Church literally upon his death-bed – he had decidedly not lived as one.