by Tony Wolf (originally published via the Atlas Obscura on October 9, 2017)

After my father died in mid-2016, the family was faced with a daunting question: “What to do with the collection?” Dad had been acquiring and restoring all manner of curious antiques since the 1960s. His vast collection filled “the studio”—a huge, barn-like building adjacent to his home in Horokiwi, New Zealand.

In recent decades, Dad’s interests had turned to stage magic props and the studio had become an unofficial museum of New Zealand magic history. Houdini-style manacles and a straitjacket hung from hooks alongside dangling marionettes. Row after row of shelves held all manner of tricks and gimmicks such as vanishing bird-cages, spring-loaded feather-flower bouquets and mysterious little boxes that could seemingly transform dice into coins and back again.

I’d inherited some of Dad’s interest in stage magic history, especially the history of “spookology,” the use of magic tricks to create the illusion of the truly supernatural; a practice made infamous during the fake séance craze of the early 20th century. When my mother decided to donate or auction many of the collection items, I began the task of cataloguing them.

It was while digging through and itemizing the collection that I discovered what might have been Dad’s most fascinating curio: a “Spook Show,” also known as a ghost show, inside a vintage leather case, measuring 20-by-17-by-12 inches.

The first object I pulled out was a black-painted, Y-shaped wooden handle with white gloves fitted on each branch. I recognized this peculiar item as a classic séance prop. Coated with luminescent paint and manipulated by an unscrupulous “spirit medium,” the glowing gloves would seem to float, ghost-like, in the gloom of a shadowy séance parlor.

I was stunned. I had been reading about these sorts of props for years, but I’d never suspected that my father had owned a set of them.

With mounting excitement, I continued to search through the case. Here was a “spirit lamp” (helpfully labeled “spirit lamp”): a small metal flashlight, its lens covered with a film of dark red cellophane, used to conjure a sinister red glow in the dark.

But that wasn’t all. The case also contained two parchment skull masks inside a battered cardboard box, alongside two pairs of skeleton-fingered gloves; green glass jars of luminous makeup; a glowing cardboard skeleton and two full skeleton bodysuits; and fragile sheets of luminous cellulose, cut into classic ghost silhouettes and trailing tendrils of “ectoplasm.”

As we continued to search through the collection, we identified more spook show props including a wooden “rapping hand”, a “talking skull” made out of papier-mâché and a number of black-painted”extending rods”, as used by unscrupulous mediums to apparently levitate objects in the darkness of a séance hall.

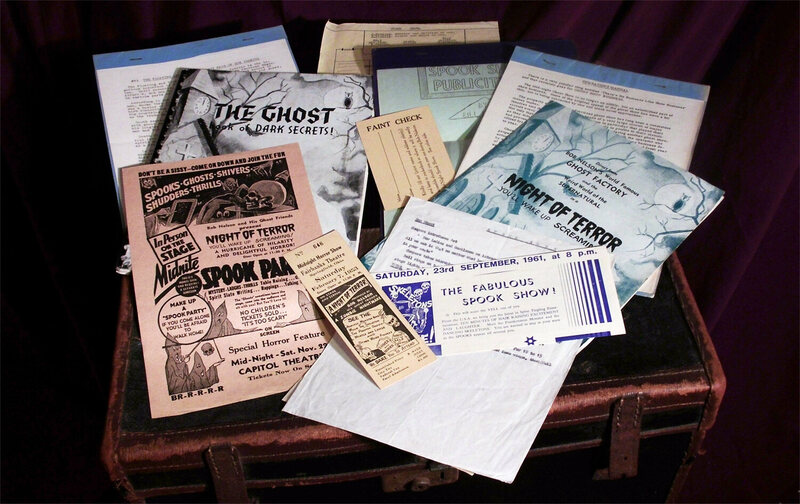

I knew that this was a very rare find and I immediately wanted to discover its provenance. There were, luckily, a few solid clues. Documents found in Dad’s files dated the props to the late 1950s. According to Bernard Reid, a New Zealand magic historian and a colleague of my father’s, he’d received the case and props from the estate of Graham Pratley, a magician based in Christchurch, New Zealand, who had performed magic, hypnotism, fire-eating, and ghost shows under the name “Gordon Graham.”

A label on one of the cardboard boxes bore the name “Nelson Enterprises,” a reference to an Ohio supply company that had been owned by Robert Nelson. During the mid-20th century, Nelson’s business was nicknamed the “Ghost Factory.”

In the years during and following the First World War, many magicians had taken exception to con-artists playing the “ghost racket” on bereaved families. Some, including Harry Houdini, crusaded against phony spiritualism. Others created their own occult-themed magic shows, in which “spirit manifestations” and other staples of the séance were overtly presented as conjuring tricks rather than as proof of life after death.

From the early 1920s until his death in the early 1970s, Robert Nelson had invented, manufactured and sold all manner of spookology gimmicks. His customers included both fraudulent mediums looking to spice up their séances and magicians seeking to outdo and expose the fakery of the spiritualists. Nelson was also a well-regarded performer in his own right. During the 1930s he had toured with a theater act called “Bob Nelson and His Ghost Friends” and later he also claimed to have served as an advisor for Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion ride.

These props, tricks, and lore persisted in the magic trade after the séance craze had faded away. They made a pop-culture comeback during the horror movie boom of the 1950s and 1960s, when ghost shows became popular as pre-show entertainment in movie theaters. Frequently outfitted by Nelson’s Ghost Factory, these traveling shows were presided over by “mad scientists”—Dr. Evil, Professor Zomby, Dr. Silkini and others. They typically combined broad comedy, magic and mind-reading trickery with the type of theatrical special effects associated with haunted house attractions today. The highlight was always the “blackout” moment when the pitch-dark theater would be filled with glowing, flying ghosts and monsters.

The midnight spook show circuit finally gave up the ghost during the 1970s and has since been largely forgotten. Director Joe Dante, however, paid it an affectionate homage in his 1993 movie Matinee, set during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and starring John Goodman as a schlock horror movie director/showman who delights in devising scary in-theater promotional gimmicks.

In more recent years, these shows have occasionally been staged at magic conferences and by indie cinemas, especially around Halloween. As movie houses employ ever more creativity in enticing patrons away from their streaming videos and home theaters, perhaps these performances will undergo a resurrection.

Most of my Dad’s “magic museum” has now been donated or auctioned to fellow collectors of magicana, but not the Spook Show. As a memento mori, it has quite a storied past.