By Tony Wolf

The evocative yin-yang juxtaposition of flowers and skulls has a curious artistic history encompassing Catholic reliquary, 17th century Dutch vanitas painting, Mexican folk-art, Edwardian art nouveau and ’60s psychedelia. In combination, they offer a startling and provocative alternative to the black-cloaked, scythe-wielding figure of the Grim Reaper, whose imagery is inextricably tied to the Black Plague and to medieval Christian notions of moral philosophy.

Efforts to trace patterns of specific inspiration are doomed to failure, so for whatever else it might be worth, here’s a general, loosely chronological survey of the flower-skull motif.

The custom of wearing chaplets (floral or foliate wreathes) as head decoration extends back at least as far as the Classical era. Numerous Greek and Roman deities and demi-gods were so represented and the tradition of awarding laurel wreathes for military, political and athletic victories became well-established.

The specific association of flowers and skulls emerges in Medieval illuminated manuscripts. By juxtaposing skulls with traditional floral and foliate motifs, the illustrators remind the viewer that death is inherent to life; though as with later church and graveyard decoration, it’s difficult to parse whether the message is one of regeneration or corruption.

By the 1600s, Dutch artists were incorporating flower and skull symbolism into their vanitas paintings. Although initially present as discrete elements, over time the motifs merged, offering perhaps the first specific examples of the flower-chaplet-bearing skull in the canon of Western art.

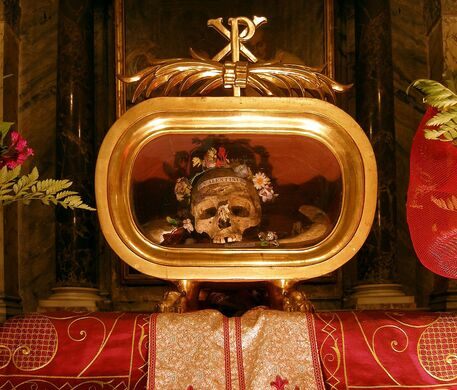

At some point during the early 1800s, excavators working in a Roman catacomb unearthed a collection of skeletal parts that became associated with the figure of St. Valentine. As was customary, items of the remains were distributed to reliquaries throughout the world; the saint’s putative skull is on display in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Rome, adorned with a floral chaplet.

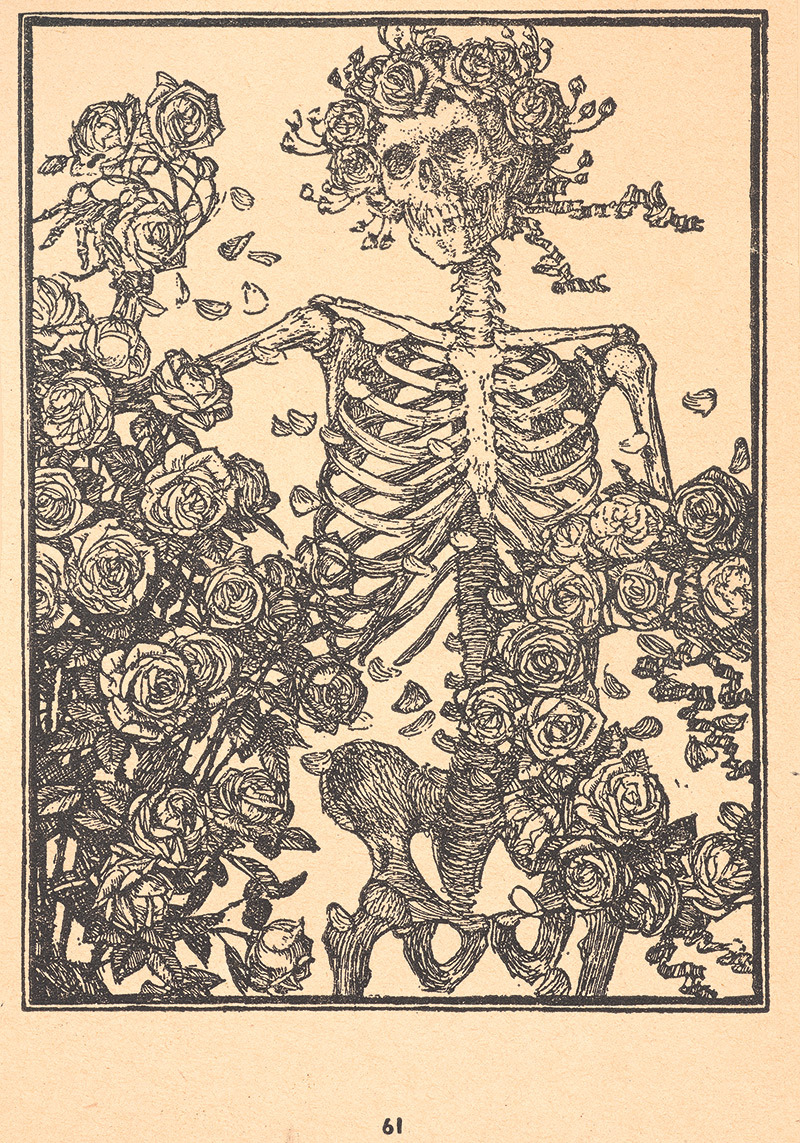

At the turn of the 20th century, artists working in the Art Nouveau style made much use of floral and foliate motifs but generally shied away from skull imagery. A notable and joyous exception was the English illustrator Edmund Joseph Sullivan (1869–1933), whose pictures for a 1913 edition of Fitzgerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám translation included a striking, fantastical image of a skeleton wearing a crown of roses while assembling a rosy wreath.

Sullivan’s illustration accompanied the following poem:

XXVI

Oh, come with Old Khayyám, and leave the Wise

To talk; one thing is certain, that Life flies;

One thing is certain, and the Rest is Lies;

The Flower that once has blown for ever dies.

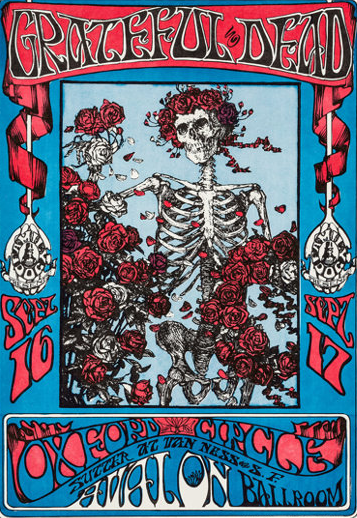

Sullivan’s art might have been forgotten during the 20th century, had it not been appropriated by artists Stanley “Mouse” Miller and Alton Kelley as poster imagery for an up-and-coming rock group known as the Grateful Dead in 1966. Kelley added lettering and Miller colored the image, and the rest is pop-culture history.

The phenomenal success of the Grateful Dead turned the flower-crowned skull into a potent icon of the ’60s counterculture, appearing on everything from psychedelic album covers to home-made t-shirts.

From there it was a short sub-cultural jump into surfing and skateboarding art, not to mention tattoo flash:

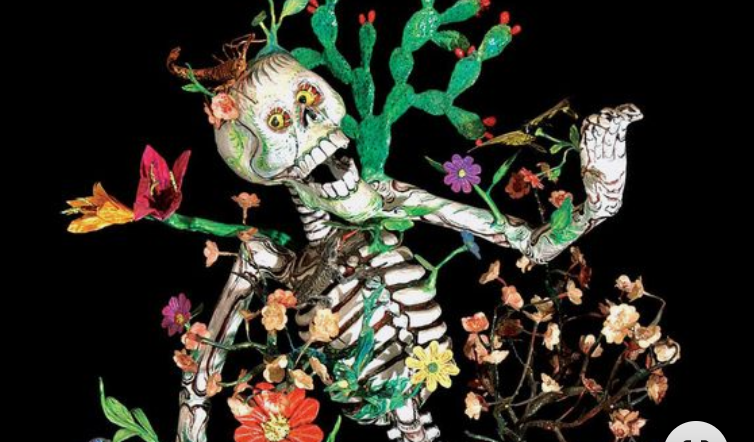

During roughly the same mid-late 20th century period, the Mexican Dia de Muertos festival was undergoing a cultural renaissance inspired by a panoply of sources including the 1890s-vintage social satire cartoons of José Guadalupe Posada. The artist’s most famous image, la Calavera Catrina, mocked the pretensions of social climbers who adopted European fashions such as enormous floral hats.

Several decades of artistic inspiration and innovation later – most especially via the work of Mexican artist Felipe Linares during the 1970s and ’80s – it has become common for Dia de Muertos celebrants to wear elaborate calavera facepaint and floral crowns. Not incidentally, Felipe’s father Pedro had invented the whimsical, chimerical alebrije figures during the 1930s.

… and the emergent folk-saint Santa Muerte is also occasionally depicted wearing a floral crown, or possessing a halo of flowers.

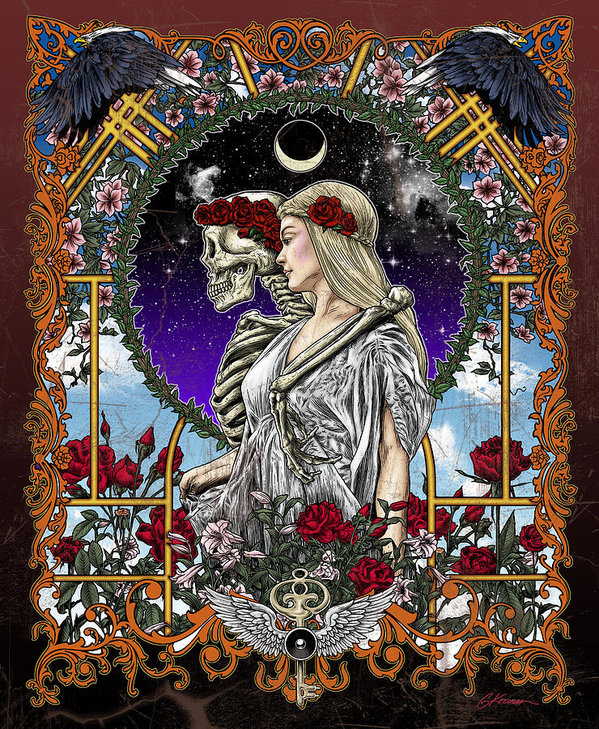

By affirming the natural interplay of life and death, with the flowers arguably representing a secular, poetic notion of the soul – as in, the traces of individual lives, left behind in nature and culture and in memory, worthy of respect and celebration – the flower-skull motif seems a fitting emblem for the emerging alternative death counterculture.

Won’t you join the dance?