Oh, that sweet fragrance of falling petals….

With kind words, it is ended. Farewell.

The time to go is now.

- Lee Hyong-Ki [1963]

It may be that the people who would most benefit from symbolic ritual are those who are least likely to partake in it. The inclination towards formal, poetic gestures in moments of truth may very much depend on who you were when you first read a book that changed everything, or whether you have an intuitive understanding of “serious play”, or what happened when you first stepped into terra incognita.

If you feel a need for permission or encouragement to take that step, though, please consider these words to be that. I know the immediate and lasting values of personal memorial rites; undertaking your own ritual for the dead is a strong step towards comfort and closure. In the longer term, these rites also form enduring, positive memories in association with the end of life.

If you’re there, one way or the other – if, in the words of C.W. Nicol, your soul demands a dramatic gesture – I offer the following prescription for a very simple memorial ceremony. All you need is a special place in nature, a bowl, a poem, a collection of flower petals and a small glass bottle.

Inspiration

When I was younger I spent some time, over the course of many years, in the city of Christchurch, on the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Sometimes called “the most English city outside of England”, the Christchurch of my memory was a vibrant city of Victorian architecture and the host of events such as the Festival of Romance and the World Buskers (i.e. Street Performers) Festival. I have especially fond recollections of the Arts Center, established in the Gothic Revival former campus of Canterbury College, of a vivid storytelling walk through the Botanical Gardens and of a truly entertaining and educational sightseeing tour riding on one of the quaint street trams, crossing several times over the River Avon, which winds through the heart of the city.

Tragically, on the early afternoon of Tuesday 22nd February, 2011, Christchurch was struck by a major earthquake that killed 185 people. The disaster especially decimated the central city, causing nearly NZ$45 billion in property damage.

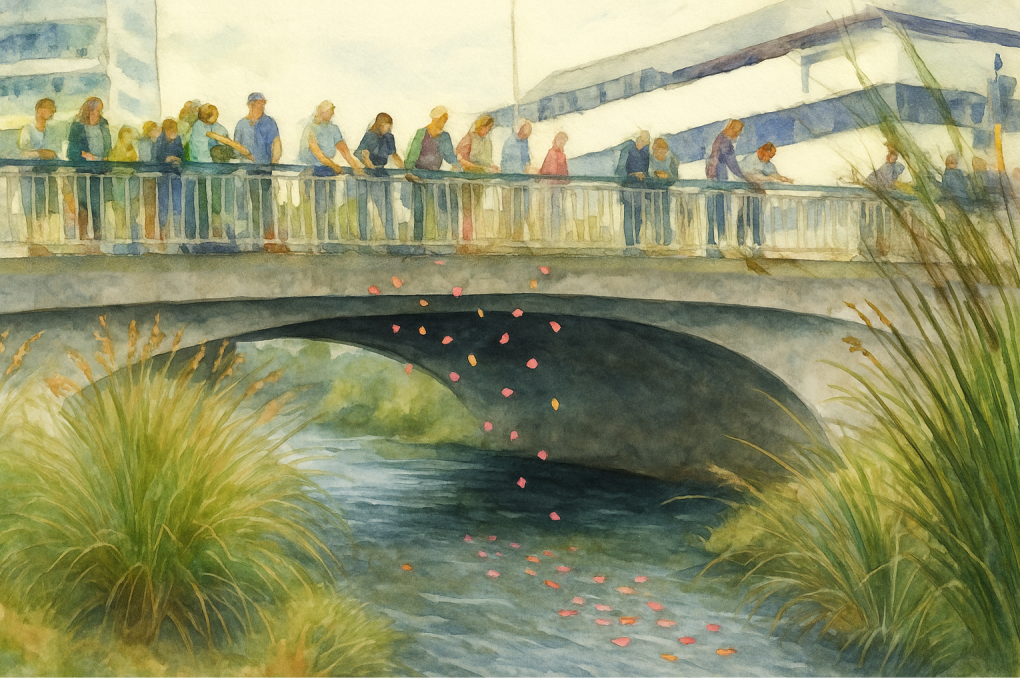

In the aftermath was born a new tradition of mourning and remembrance, known as the River of Flowers. Each year, on the anniversary of the earthquake, Christchurch citizens gather along the banks and on bridges over the Avon River and toss flowers and flower petals into the water, in commemoration of the lives lost and in celebration of their city’s enduring spirit.

In early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns began preventing people from gathering for traditional funerals and memorial ceremonies, I devised the Falling Flower ritual as a private or small-group alternative for people who were grieving. Although several elements are unique to the Falling Flower, the essential motif was directly inspired by the River of Flowers ceremony in Christchurch.

Preparation

Because people often give flowers as sympathy gifts after bereavements, this is a nice way to extend that sentiment for a while; you can also pluck (and, if you wish, dry) some of their petals. Flowers and petals can also easily be sourced by keeping an eye out during walks after summer storms. I have a special bowl, natural terracotta on the outside and black on the inside, for storing the petals as they dry.

Because dried flowers lose their scent, you may wish to add a few drops of essential oil or a scattering of incense ash to the petals before performing the memorial ritual.

The bottle is for a beverage or liquid that makes sense to you in this context. Mine contains honey, as a reminder of the sweetness of life. In late 2023 I attended a Falling Flower ritual in which the bottle held cold water, which had been the decedent’s favorite refreshment.

The Ceremony

Having gathered your petals and filled your bottle, then:

Step 1: Select your poem. There are no hard and fast criteria here; if it feels right, it’s right.

Step 2: Travel to the chosen site. Find an appropriate spot and time; this may mean at sunset, crouched on a riverbank with no signs of industry, or standing at mid-day on the center of a bridge in the heart of London, or at midnight perched on a tree branch overhanging a quiet country stream. It may mean the top of a windy hill at dawn, or standing next to a tree in your own backyard.

Step 3: Take a moment and bring to mind the being you wish to memorialize. Breathe. Smell the flower’s scent. Listen.

Step 4: Look at the flower/petals and speak the poem, and – of course – say anything else you wish to say.

Step 5: Release the flower/petals. If you wish, you can open your hand into the memento mori mudra; if so, complete the gesture with the carpe diem mudra.

Step 6: Watch the flower/petals being carried away by wind or water, or as they fall to the earth. Know that as the petals are returned to nature, so do we all return, in time, and that those who have gone before us live on in our memories.

Step 7: Taste the beverage, then do as you will. Consider starting a new, creative project in honor of the deceased; transmuting grief into memorial art is powerful emotional alchemy.

You may wish to establish a tradition of performing the Falling Flower ritual as an annual remembrance, on the anniversary of the decedent’s birth or death, or keep a store of dried petals in your bowl on an ongoing basis, for use as and when it may be of comfort. I keep my bowl of dried petals and a glass bottle of honey on my shrine, for these occasions.